What is a body to do with itself in a space like this?

Shannon Bool

Crimes of the Future

Non-verbal dialogues between bodies, architecture and materials are key to Shannon Bool’s work. The connection between highly technologized and historical production processes and materials construct complex experiences of material, space and bodies, resulting in the permeability of seemingly fixed definitions of gender, culture and identity. In the process, the body literally becomes the “site of images.”

The title of the current show, “Crimes of the Future,” and of the eponymous large-format tapestry cites the movie by David Cronenberg released in 1970. Shannon Bool focuses on architecture as a projection screen and choreographer of the actions and identity of the bodies of the protagonists that are at first “meaningless.” The architectural style of “brutalism” plays a central role. The term “brutalism” derives from the French “béton brut,” meaning “raw concrete.” Evolving in the 1920s as a modernist movement, brutalism aimed at providing the experience of “mental liberation”, “true seeing”, “sensuality instead of commerce”.

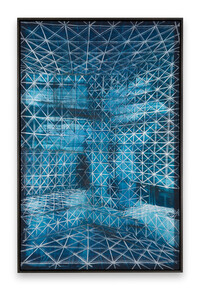

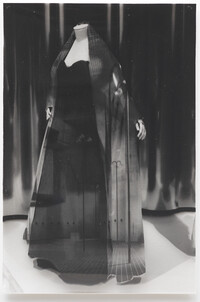

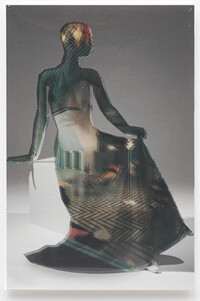

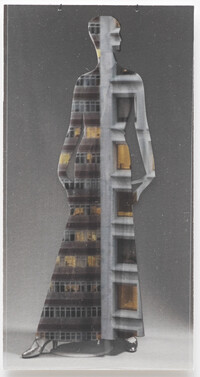

The motif of Shannon Bool’s tapestry “Crimes of the Future” was generated on the computer and is based on a photograph of a presentation at the Yves Saint Laurent Museum in Paris. Shannon Bool arranges the modernist-minimalist figurines, which themselves are already a surrogate of the female body, to a new projection screen by creating a collage on the “inside” of the silhouettes with detailed views of sacred architectures of brutalism, such as the Wotruba Church in Vienna, the Neviges Church in Düsseldorf by Gottfried Böhm, or the Second Goetheanum by Rudolf Steiner. The motif triggers a cascade of associations. The original figurines as “pure” projection screens were already compared to Madonnas of consumerism. This “nakedness of meaning” is now replaced by the nakedness of brutalism’s concrete architecture. Shannon Bool transfers and alters the art-historically anchored approach of experiencing space and architecture with the body through the production process of the tapestry “Crimes of the Future.” The computer-generated motif is produced with the highly technologized Jacquard weaving method that translates digital space into a haptic relief. On the computer, the extreme enlargement of the motif generated a rasterization of the image that becomes part of the real work. Shannon Bool’s tapestry thus gives rise to a paradoxical corporeal experience between digital and real space, which literally “collapse” in the mental space of the viewer.

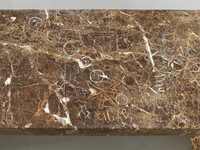

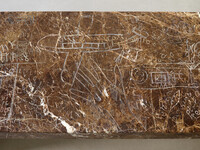

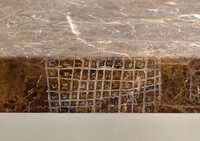

The marble object “Fragments of NOF4” consists of complexly structured Emperador marble which Shannon Bool had fabricated into a bench. An all-over pattern of scratches and engravings covers the marble. All motifs cite a huge wall drawing at the psychiatric clinic in Volterra, Italy, that counts as one of the most famous works of “outsider art” and was produced by the patient Oreste Fernando Nannetti between 1959 and 1972. In art history, drawing was regarded as a “first sketch” making the immaterial world of thoughts visible to the outside. Drawing in the form of scratching and engraving literally appropriates the material space. Moreover, Shannon Bool’s motif of the bench defines a real place that is “occupied” by the tangle of thoughts in writing and motifs that have become “matter.” The text fragments are the first layer covering the bench, they are messages and patterns, “erased” at some places and superimposed with motifs of flying objects, such as astronauts, animals and figures.

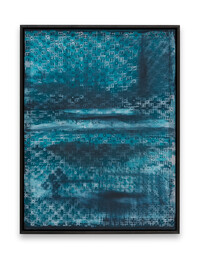

Shannon Bool’s series of abstract “grid” and “waffle” paintings are based the architecture of different brutalist structures built in the 1960s, which were deconstructed on the computer. The compositions are “collaged” on the computer turning the functional architecture into an abstract pattern. Having cast off its “sacred transcendence” in this way, a tongue-in-cheek, savvy play with the “sacredness” of abstract art begins. The grid structures are created as “blind painting.” The support is covered with wax and removed only after the painting process is over. It is semitransparent and conceals a mirror that subtly reflects the surroundings of the work. The actual space and body of the viewer become components of the work. Shannon Bool’s conceptual painting originates in a precise work process that simultaneously involves the “unforeseeableness” of abstract painting.

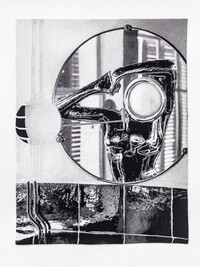

The new tapestry entitled “Dawn” is based on the same work process. The motif shows the interior view of the famous building E1027 by the architect and designer Eileen Gray, which is regarded as an icon of modern architecture and was built in 1929. Already in the motif of “Dawn,” different spatial realities collapse. In the computer-generated composition, Eileen gray’s famous “Satellite” mirror of design history is combined with the reflection of the actual environment and the illusion of a figurine, which is positioned exclusively into the reality of the mirror. This engenders an endless projection between body, space and identity.

In the architecture of the gallery space, Shannon Bool subtly places a minimalistic, black glazed ceramic sculpture. The shape derives from artificial housing for bats, while the shimmering black glaze cites the interior design of Eileen Gray’s E1027 Villa. In a certain respect, the objects become a “window” to uncertainty. Bool’s Bat House functions on the level of citations, namely, an art-historical reference to Malevich’ “Black Square” from which “everything was possible,” and continues to play with its original function as housing for bats. It symbolizes uncertainty, first of all of the night, and currently as the possible initial vector of the Covid-19 virus.

The collapsing of different realities is continued in Shannon Bool’s new collages. The small-format works consist of overlapping photographic prints on baryte paper and foil, so that the figurines with architectures such as the skyline of Hong Kong, Goetheanum II, Neviges, the Lipstick Skyscraper in New York, become unique items.

Shannon Bool’s work has become known through numerous exhibitions and museum collections. Her works are represented in museums such as the Museum für Moderne Kunst Frankfurt, the Metropolitan Museum New York, the Musée d´Art Moderne Montréal, the Kunstmuseum Bonn, the Lenbachhaus Munich or the Bundeskunstsammlung. Currently, the Agnes Etherington Art Centre in Kingston, Canada, is featuring a solo exhibition. Previous solo shows were presented at the Kunstverein Braunschweig in 2019 and as early as 2011 at the Kunstverein Bonn and the GAK Bremen. Shannon Bool, who was born in Canada in 1972, studied at the Städelschule in Frankfurt, which is renowned for its conceptual approaches, until 2003 and has been professor of painting at the Kunsthochschule in Mainz since 2017.